Nalanda University : The Storyline

More than 500 years before even the famous Oxford University was founded, India’s Nalanda University was a home to nine million books and attracted 10,000 students from around the world.

Founded in 427 CE, Nalanda is considered the world’s first residential university, a sort of medieval Ivy League institution home to nine million books that attracted 10,000 students from across Eastern and Central Asia. They gathered here to learn medicine, logic, mathematics and – above all – Buddhist principles from some of the era’s most revered scholars. As the Dalai Lama once stated: “The source of all the [Buddhist] knowledge we have, has come from Nalanda.”

Nalanda University : Students and their origins

Interestingly, the monarchs of the Gupta Empire that founded the Buddhist monastic university were devout Hindus, but sympathetic and accepting towards Buddhism and the growing Buddhist intellectual fervor and philosophical writings of the time. The liberal cultural and religious traditions that evolved under their reign would form the core of Nalanda’s multi-disciplinary academic curriculum, which blended intellectual Buddhism with a higher knowledge in different fields.

The ancient Indian medical system of Great Ayurveda, which is rooted in nature-based healing methods, was widely taught at Nalanda and then has migrated to the other parts of India via alumni. Other Buddhist institutions drew inspiration from the campus’s design of open courtyards enclosed by prayer halls and lecture rooms.

Aryabhata, considered as the father of Indian mathematics, is speculated to have headed the university in the 6th Century CE. “We believe that Aryabhata was the first to assign zero as a digit, a revolutionary concept, which simplified mathematical computations and helped evolve more complex avenues such as algebra and calculus,” said Anuradha Mitra, a Kolkata-based professor of mathematics. “Without zero, we wouldn’t have computers,” she added.

“He also did pioneering works in extracting square and cubic roots, and applications of trigonometrical functions to spherical geometry. He was also the first to attribute radiance of the moon to reflected sunlight.”

This work would profoundly influence the development of mathematics and astronomy in southern India and across the Arabian Peninsula.

The university regularly sent some of its best scholars and professors to places like China, Korea, Japan, Indonesia and Sri Lanka to propagate Buddhist teachings and philosophy. This ancient cultural exchange programme helped spread and shape Buddhism across Asia.

Credits : Dinodia Photos/Alamy

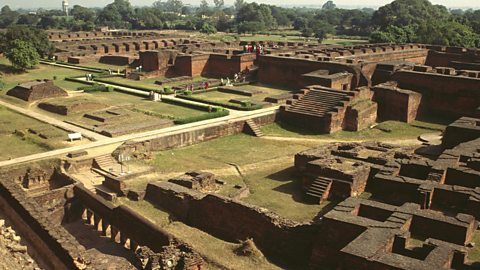

Credits : Dinodia Photos/AlamyThe archaeological remains of Nalanda arenow a Unesco World Heritage site. In the 1190s, the university was destroyed by a marauding troop of invaders led by Turko-Afghan military general Bakhtiyar Khilji, who sought to extinguish the Buddhist centre of knowledge during his conquest of northern and eastern India. The campus was so vast that the fire set on by the attackers is said to have burned for three months. Its vast library and its 9 million books and scriptures took 3 months to burn out.

Today, the 23-hectare excavated site is likely a mere fraction of the original campus, but ambling through its multitude of monasteries and temples evokes a feeling of what it must have been like to learn at this fabled place.

The library’s nine million handwritten, palm-leaf manuscripts was the richest repository of Buddhist wisdom in the world, and one of its three library buildings was described by Tibetan Buddhist scholar Taranatha as a nine-storey building “soaring into the clouds”. Only a handful of those palm-leaf volumes and painted wooden folios survived the fire – carried away by fleeing monks. They can now can be found at Los Angeles County Museum of Art in the US and Yarlung Museum in Tibet.

![REY Pictures/Alamy The Dalai Lama once said: "The source of all the [Buddhist] knowledge we have, has come from Nalanda." (Credit: REY Pictures/Alamy)](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/images/ic/480xn/p0f3vn4g.jpg.webp) REY Pictures/Alamy

REY Pictures/AlamyThe acclaimed Chinese Buddhist monk and traveller Xuanzang studied and taught at Nalanda. When he returned to China in 645 CE, he carried back a wagonload of 657 Buddhist scriptures from Nalanda. Xuanzang would go on to become one of the world’s most influential Buddhist scholars, and he would translate a portion of these volumes into Chinese to create his life’s treatise, whose central idea was that the whole world is but a representation of the mind.

His Japanese disciple, Dosho, would later introduce this doctrine to Japan, and it would spread further into the Sino-Japanese world, where it would remain as a major religion ever since. As a result, Xuanzang has been credited as “the monk who brought Buddhism East”.

“The Great Stupa actually predates the university and was built in the 3rd Century CE by Emperor Ashoka. The structure had been rebuilt and remodelled several times over eight centuries,” said Anjali Nair, a history teacher from Mumbai, whom I had met at the site. “Those votive stupas contain the ashes of the Buddhist monks who had lived and died here, dedicating their entire lives to the university,” she added.

More than eight centuries after its demise, some scholars contest the widely held theory that Nalanda was destroyed because Khilji and his troops felt its teachings competed with Islam. While uprooting Buddhism may have been a driving force behind the attack, one of India’s pioneering archaeologists, HD Sankaliya, wrote in his 1934 book, The University of Nalanda, that the fortress-like appearance of the campus and stories of its wealth were reasons enough for invaders to deem the university a lucrative spot for an attack.

Sugato Mukherjee

Sugato Mukherjee“Yes, it is difficult to assign a definitive reason for the invasion,” said Shankar Sharma, the director of the onsite museum, which displays 350 artefacts of the more-than 13,000 antiquities it houses, which were then salvaged during Nalanda excavations, such as stucco sculptures, bronze statuettes of the Buddha, and ivory and bone pieces.

While the Huns came to plunder, it is difficult to conclude whether the second attack by the King of Bengal was the result of a growing antagonism between their Shaivite Hindu sect and the Buddhists at the time. On both occasions, the buildings were restored, and the facilities were expanded after the attacks with the help of imperial patronage from the rulers.

“By the time Khilji invaded this sacred temple of learning, Buddhism was on an overall state of decline in India,” Sharma said. “With its internal degeneration, coupled with [the] decline of the Buddhist Pala dynasty that had been patronising the university since the 8th Century CE, the third invasion was the final death blow.”

Sugato Mukherjee

Sugato Mukherjee